The author’s views are entirely his or her own (excluding the unlikely event of hypnosis) and may not always reflect the views of Moz.

It’s common to hear SEOs discuss the “increasing dominance” of big brands in SEO, and how smaller companies just can’t break into the rankings like they used to. Google even put out a “domain diversity” algorithm update a couple of years ago to address the issue, and people like me have shown time and time again how metrics like branded search volume and domain authority — typically signs of a big, well-known company — are key predictors of search performance.

This post, though, is to share some surprising data we’ve surfaced at Moz suggesting that, actually, right now is the best time in years to be an outsider in SEO.

What is domain diversity?

I think there are two appealing ways to define domain diversity, and we’ll look at data for both.

Normally, “domain diversity” is used to refer to a greater number of unique sites appearing in a given SERP. For example, if you have three results from Pinterest and two from eBay on the first page, that is an example of very low domain diversity. I’ll talk about this as “per-SERP” domain diversity below.

The other type of domain diversity I’d like to discuss is the extent to which the biggest sites dominate SEO in general. If the same few sites are ranking top 5 for any query you can think of, that doesn’t necessarily mean low per-SERP domain diversity, but it is still a very homogenous and inaccessible search landscape. I’ll talk about this as “overall” domain diversity, but this is also the domain diversity metric shown on MozCast.

Per-SERP domain diversity

For this measure, we’re using the percentage of page one results which are the first appearance of that subdomain. So for example, if the first page of results has 10 organic listings, of which eight are unique but two are en.wikpedia.org, that’s a score of 90% (i.e. 9/10). Another way of thinking about this same metric is the average ratio of unique subdomains (9) to total subdomains (10). The dataset used throughout is the MozCast corpus.

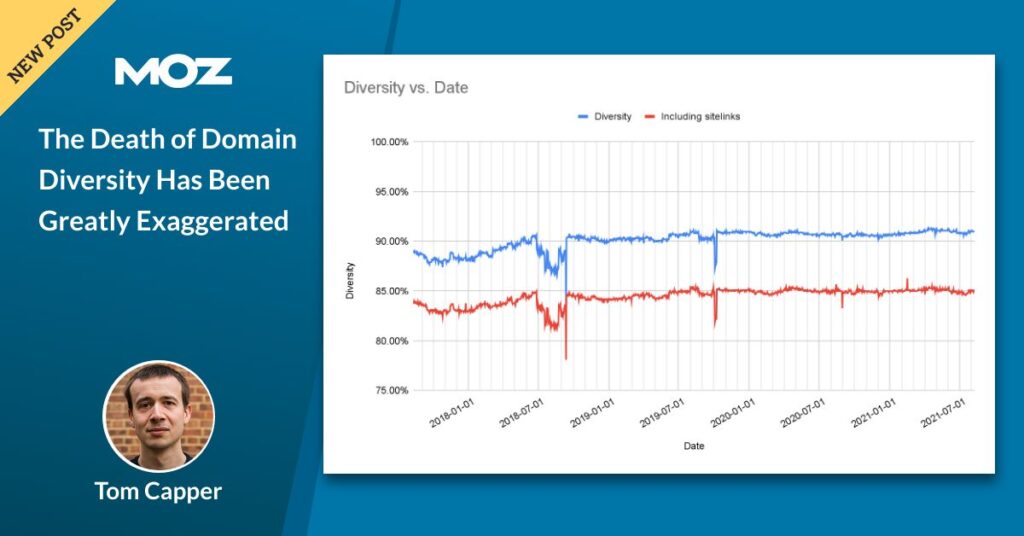

Here’s how that looks for the last four years, up to August 2021:

To my eye, this is almost incredibly level. For virtually the entirety of 2019, 2020, and 2021, we’ve hovered between 90 and 92%. That’s roughly equivalent to each SERP having one duplicated subdomain. I’ve also included the same statistic if we count sitelinks, which obviously is a little lower as sitelinks always repeat the main site domain, but this is still remarkably consistent.

There’s a five-day dip between October 4 and October 8, 2019, and a longer period of fluctuation starting June 28, 2018, but neither line up particularly closely with any major algorithm update or SERP feature change, and both were ultimately corrected.

Google’s own Site Diversity update on June 6, 2019 barely registers, with a 0.5% impact on the day:

For me though, the main story here is the incredible consistency. For this metric to have been so level for so many years, it feels very likely that this has been something Google has explicitly targeted.

Overall domain diversity

For overall diversity, rather than looking at the average ratio of unique subdomains to total subdomains per SERP, we’ve done it across every page one result in the corpus. So, for example, taking 100 results from 10 SERPs, a score of 30% would mean that there were 30 unique subdomains.

This chart has a bit more going on, but you can see that the current level of diversity is the highest in years (with the exception of a brief spike in 2020):

We last saw diversity this high in mid-2017, and we’ve not seen levels significantly higher since late 2016.

As with per-SERP diversity, much of the variance on this chart doesn’t line up with any known algorithm update. However, there are a couple of recent notable exceptions:

Two of the biggest one-day changes we’ve seen are associated with Google “glitches”. Some of the more gradual changes happen around known algorithm updates, but the biggest of all seemingly went totally unnoticed by the SEO industry.

Bonus: The Big 10

Another way of measuring domain diversity is by the percentage of results that are one of the 10 most common subdomains in MozCast. What features on this list varies over time, but for context, right now it looks like this:

-

en.wikipedia.org

-

www.amazon.com

-

www.facebook.com

-

twitter.com

-

www.webmd.com

-

www.healthline.com

-

www.yelp.com

-

www.walmart.com

-

www.mayoclinic.org

-

www.pinterest.com

This metric is also lower than it has been for a while, albeit not quite so extreme:

That big drop in 2018 coincides with the introduction of video carousels as non-organic results, heavily reducing YouTube’s presence as a big player. (It now sits just outside our top 10).

What does this mean for SEOs?

If you still feel that small brands are being crowded out in your industry, you could be right. We’ll be publishing more posts digging into narrower versions of this data — industries, specific big sites, and result types. Indeed, I’d love to hear what you’d like to see more of over on social media.

For now, though, the main takeaway is that the last few years — even with their focus on E-A-T and other factors we consider easier for bigger brands — have far from wiped out diversity in the SERPs. On the contrary, it’s rarely looked better.